drawing of sun inside trees of a guitar original artist

The creative process begins as soon as Freeman Vines touches the wood.

"Nobody believes me. The wood actually lives. Each wood has an inner spirit, and if you listen you will find some magnificent stuff on it," Vines said, his voice thick with the accent of rural North Carolina, his home for 78 years and his family's home since they were enslaved.

A luthier and artist, he creates sculptural guitars so distinctive that they have become a traveling exhibition and are featured in a new book, "Freeman Vines: Hanging Tree Guitars," published by The Bitter Southerner, a website devoted to the culture of the New South, and the Music Maker Relief Foundation.

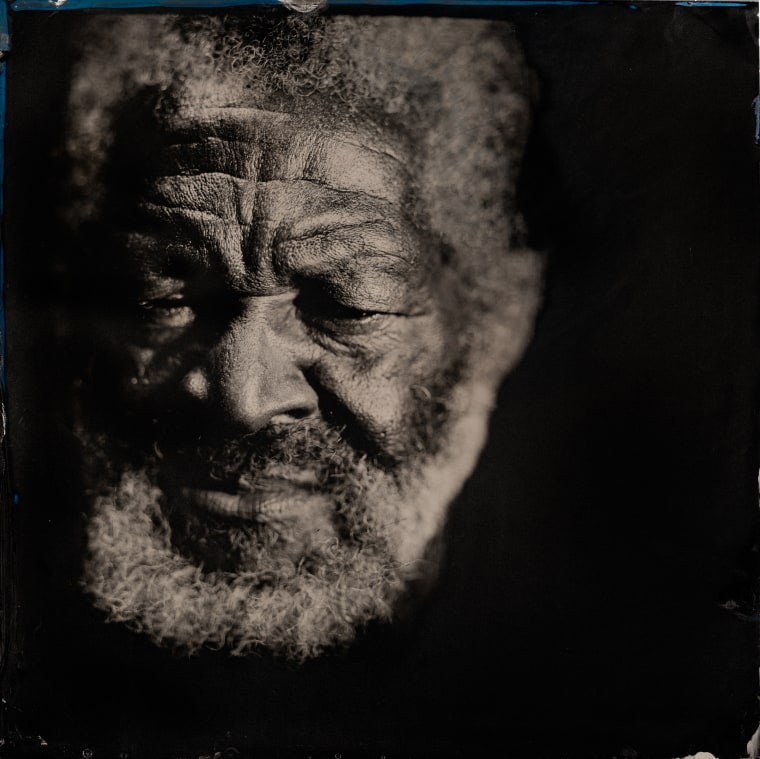

The title of the book and the exhibit refer to the haunted wood from a lynching tree that Vines used to make a series of guitars. The book is filled with beautiful tintypes of the luthier, his creations, the land and the raw poetry that comes from Vines' mouth:

If you ever notice

The oak tree stays an oak,

a pine stays a pine.

A man is the most destructive, evilest thing, that's ever been.

Know how I know?

I'm one.

Vines said he always listens to the wood, gets to know it a little — and then begins his relationship with it.

"You become acquainted with the wood. Sand it off to see what it is showing you," said Vine, who uses wood from nearby trees, tobacco barns, mule troughs and radio parts, working with homemade tools.

"The wood does not like commercial tools," he said. "I've used a jigsaw and a band saw, but that steals the opportunity on what it is going to be. The wood's characteristics don't come out. Sometimes the wood uses bad language. Some is easy to get along with.

"I enhance it a little, but that's all. I respect the characteristics. I don't try to alter the wood no way."

He imbues the instruments with his personal history, too.

His name, he said, is really Free Man, not "Freeman," a name passed down the line to him from the days of slavery, his mother told him. He lives in Fountain, a rural town of just over 400 people, in Pitt County near the plantation that once held his family. He has traveled the country chasing music, but he always returned to this blood-soaked land where his mother was a sharecropper for years and then a "house woman," or domestic, where his ancestors were slaves and where his own life at times was so obviously controlled by others.

He was imprisoned at age 14. "I was underage in a grown folks' penitentiary. If you were 2 years old and the white man said you did a crime, you had to go," he said.

I learned to read and write in the penitentiary.

The college I went to is spelled C-H-A-I-N G-A-N-G.

And in the book, after talking about the Klan: A white man is a dangerous man. If you stay out of his damn territory, out of his world, you can make it.

He thought he wanted to be a guitar player, a blues man, but he admits he was never very good. Much of his life, he worked at odd jobs, did manual labor, dug ditches and worked as a migrant worker on the East Coast. He trained and then worked in the 1970s and '80s to restore old vehicles for car collectors.

"All I wanted was the money," Vines said.

But maybe he wasn't really living? His first quote in the book is: A person has to have a purpose to live.

One day as he walked out of a shop he heard a sound that struck him so deeply that he longed to replicate it. So in 1958, when he was 16, he began his "supernatural experience" with wood and with fashioning stringed instruments.

A year or so ago, Vines went to a man who was related to the Jefferson family, which once owned Vines' family during slavery. The man had some wood from a 100-year-old tree. According to the book, Mr. Jefferson said: "Vines, I'm gonna tell you now. You're black and I'm white. That wood there came off a hanging tree."

Vines didn't believe him. But he took the wood home to begin his process.

That night as he sanded the wood, Vines said, "I felt a whole lot of different things. It sounded like somebody dragging its feet when I was working on it. The dogs barked."

Vines wanted to know where the lynching tree had stood, but he wasn't comfortable asking people, and most of the people he asked weren't comfortable talking about it. Then a local woman took Vines and Timothy Duffy, the book's photographer, to the place where the tree had stood and a man had been lynched. Vines wouldn't walk up to the spot. Duffy found other information in a newspaper archive.

"I told him I didn't want to hear no more," Vines said. "He died a terrible life."

Duffy is also founder of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, which works to preserve the musical traditions of the South by directly supporting musicians. He saw the hanging tree guitars and the story as an opportunity for healing, in the vein of resistance art. He wanted people to know the details.

"If you don't talk about this, you can't heal," Duffy said.

He discovered that the man hanged from the lynching tree was Oliver Moore, 29, a Black man accused of raping two white girls. Newspaper accounts say a mob of 200 men took Moore from the jail on Aug. 19, 1930, hanged him and riddled his body with bullets 200 yards from his house.

When asked about the hanging tree wood, Vines repeats what he said in the book:

I say it's strange he's dead and the tree is still living.

Vines won't forget the hanging tree, but he's moved on, to listen to new old wood and to relish in the fact that today an old Black man in Fountain could have an exhibit in a museum. His work is on display at the Greenville Museum of Art in Greenville, North Carolina, through December, and then it's expected to visit museums in Portsmouth, Virginia, and Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

"I was tickled pink," he said about finding out that his work would be exhibited. "Ma always said if you ain't tickled pink and happy, you're lonely."

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/why-artist-built-guitars-out-tree-was-once-used-lynching-n1242580

0 Response to "drawing of sun inside trees of a guitar original artist"

Post a Comment